BOOT CAMP - REALITY IN JEOPARDY

By: Glenn B. Knight

The Atlantic Coast Line train squealed to a stop

beneath a wooden sign lettered "YEMASSEE" and the porter with a wink in

his voice wished us a good day. It was the last civil greeting I would

hear for 13 weeks. Stepping on to the platform, we were entering a new

and perversely strange world of barked baritone falsetto, and the

original "in your face" attitude. I remember wondering what the

passengers on the train must have been thinking as they click-clacked

out of the station behind our line of terrified young men. More than

likely they paid no intention to the seminal event of our adult life.

Preparation was certainly not a problem. My

recruiter--Staff Sergeant Peter Paul Coconis-- had explained it all to

me. I had seen it in Jack Webb's movie "The DI". For five years I

studied military drill and ceremonies as a Civil Air Patrol cadet. I had looked at the Platoon books in the recruiter's office and I read everything I could about this thing called Marine Boot Camp.

Sure, like everyone else on the platform I was scared but it was too late now! After all, I had intended to join the Air Force

and become some kind of electronics technician I had aced the

electronics portion of the entrance test and the only thing open in the

Air Force in 1962 were electronics jobs for those who could qualify.

After receiving the test results in the mail along with a vague

invitation to come in to the Air Force Recruiting Office to talk about

a potential opening in the next year or so, I did just that. In fact, I

did it six times and each time there was a sign on the door explaining

why Staff Sergeant Stewart W. Crim was out of the office.

On my third visit to the second floor of the old Post Office Building in Lancaster,

Marine Staff Sergeant Peter Paul Coconis looked out his door and

offered me a seat. The next visit this same friendly gent (who just

happened to look like a Greek  God

in his dress blues) started filling me in on the advantages of the

Marine Corps. After checking my scores to make sure I wasn't just

bothering Sergeant Crim, he offered to deliver a message. Before my

next, and last trip, to see the Air Force Recruiter I had an argument

with a former girlfriend's father, an ex-sailor, who called me a wimp.

I decided then to get into the service, do my time, get out and become

a Pennsylvania State Trooper

to prove to him that I was no wimp. Unfortunately, I was more than 6

feet tall, weighed in at just over 100 pounds and never played

sports--sort of your classic wimp.

God

in his dress blues) started filling me in on the advantages of the

Marine Corps. After checking my scores to make sure I wasn't just

bothering Sergeant Crim, he offered to deliver a message. Before my

next, and last trip, to see the Air Force Recruiter I had an argument

with a former girlfriend's father, an ex-sailor, who called me a wimp.

I decided then to get into the service, do my time, get out and become

a Pennsylvania State Trooper

to prove to him that I was no wimp. Unfortunately, I was more than 6

feet tall, weighed in at just over 100 pounds and never played

sports--sort of your classic wimp.

Sergeant Coconis greeted me with a strong hand

shake, a smile and a promise that Marine Boot Camp could make a man out

of anyone even me. Baited, hooked and reeled in, the next thing I

remember was standing with my right hand in the air at the Philadelphia

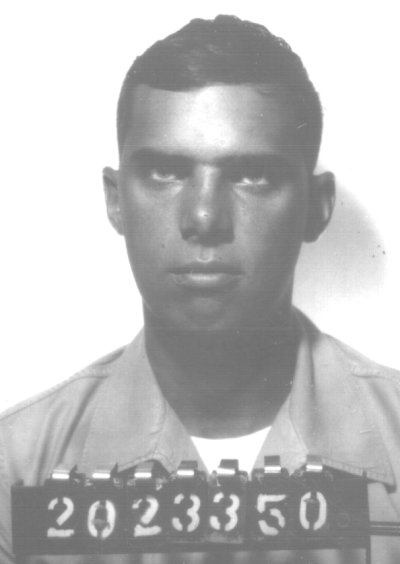

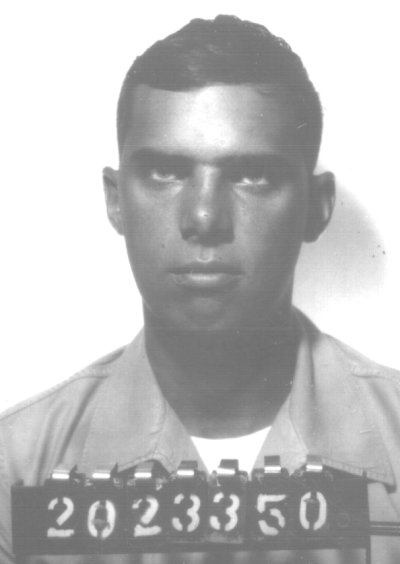

Naval Yard. I took the train back home on August 14, 1962 as Private

Glenn B. Knight, USMCR(J). Boot camp awaited me in mid September but

until then it was PARTY TIME.

The week before I was to leave for Parris

Island, my neighbor and fellow Civil Air Patrol cadet, John Howell,

threw a going-away party (because it was a good excuse and because his

parents had left him home alone). About a half dozen or so friends

gathered at John's house and emptied a keg or so. We nipped at grain

alcohol and then went to visit Vogsie (Carol Vogeler). Her mother,

showing a great deal of sense, kicked us out and on the way back to

John's house the Fiat we were all crammed into crashed, head-on, with a

parked Chevrolet. I limped off across the Moravian

Cemetery to my grandparents' house and they took me to our family

physician, Dr. Art Griswold, at 3 in the morning, to treat my broken

collar bone. Doc had served in the Navy in World War II and at the time

was Mayor of Lititz our small

Pennsylvania Dutch community. While in his office the Chief of Police

called to alert him to an accident on Marion Street and warn him to be

on the look out for some injured drunks. Doc was a "man's man" and he

decided that I needed the Marine Corps more than I needed a police

record and he gave me a "pass". He was right.

Oh, John Howell, the guy who gave the party?

He graduated college, completed Naval OTS, was commissioned an ensign,

drove gun-boats in the Vietnamese Delta, retired from the Navy Reserve

as a commander and just recently retired from the Drug Enforcement Agency where he had been an undercover agent. Doc Griswold gave him a "pass" too.

Lou Routino and I met at the train station in

Philadelphia. We had tickets to share a sleeper room on the train to

Yemassee, South Carolina. While we shared our life histories, neither

of us really listened to the other as we made up our bunks and slept

until the porter gently knocked to tell us, "Next stop Yemassee sir".  At

that point life went on automatic and fear numbed me as we were

"greeted" on the platform of Yemassee Station and as the "cattle cars"

(actually 40 foot tractor-trailers converted to haul human cargo) drove

us to reception, some 30 miles away at Parris Island, South Carolina. A

trance took me through everything Sergeant Coconis had warned me about

the search for alcohol of any type (including after shave and cologne)

and pornographic photos (that list started with photos of girl friends)

and "POGEY BAIT" all of it confiscated. Linen and PX issue (with drill

instructors walking the cat-walk above the bins in front of us yelling

insults and calling us "lower than whale shit" and "ladies") was all

taken in stride. Even jumping in and out of bed about a bazilion times

before we were allowed to sleep until what I was later to hear

described as "Oh-Dark-Thirty". I slept like a baby until Pearl Harbor

was reenacted in our echo-chamber of a squad-bay. All three drill

instructors had positioned themselves with a metal GI can over their

heads and, at reveille, they threw them on to the linoleum floor as an

inducement for us to rise, strip our beds of linen and covers and

appear in our underwear at the foot of our beds (A.K.A. racks). Fear

was growing rapidly but the reality of the situation had not yet set

in.

At

that point life went on automatic and fear numbed me as we were

"greeted" on the platform of Yemassee Station and as the "cattle cars"

(actually 40 foot tractor-trailers converted to haul human cargo) drove

us to reception, some 30 miles away at Parris Island, South Carolina. A

trance took me through everything Sergeant Coconis had warned me about

the search for alcohol of any type (including after shave and cologne)

and pornographic photos (that list started with photos of girl friends)

and "POGEY BAIT" all of it confiscated. Linen and PX issue (with drill

instructors walking the cat-walk above the bins in front of us yelling

insults and calling us "lower than whale shit" and "ladies") was all

taken in stride. Even jumping in and out of bed about a bazilion times

before we were allowed to sleep until what I was later to hear

described as "Oh-Dark-Thirty". I slept like a baby until Pearl Harbor

was reenacted in our echo-chamber of a squad-bay. All three drill

instructors had positioned themselves with a metal GI can over their

heads and, at reveille, they threw them on to the linoleum floor as an

inducement for us to rise, strip our beds of linen and covers and

appear in our underwear at the foot of our beds (A.K.A. racks). Fear

was growing rapidly but the reality of the situation had not yet set

in.

Later that morning I hit the brick wall of

recognition. Seated in a chair at the Triangle PX Barber Shop I could

feel my Elvis-esque pompadour flutter across both ears three more

swipes and my trademark DA was merging with the kinky and soft, crimson, brunette and blond tonsorial remains of my Platoon

mates. As we left that building we were indistinguishable one from the

other. We had no individual identity, only shades of color and that

didn't matter. Our only claim to life itself was that we were part of

Platoon 387, Third Recruit Training Battalion, Recruit Training

Regiment, Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina.

Good God, what had I done. No ex-girlfriend's father was worth this.

I'd have gone AWOL if I could have figured out how to do it. (At

Reception, even before we met our own drill instructors they were kind

enough to tell us that it was called Parris Island for a reason--the causeway that our bus brought us in on was the only land link and it was guarded by real Marines with 45 cal. pistols

and riot shotguns. The swamps around the island were populated with

hungry 'gators who long ago had developed a taste for young recruits.

Our choices for leaving the island were: 1) in the belly of a 'gator,

2) in a pine box, 3) in both custody and disgrace or 4) as a United

States Marine sitting proudly in a Greyhound bus enroute to Infantry

Training at Camp Geiger,

North Carolina). [In 1963, when I graduated as a Marine, boot camp

leave was not granted until after MCT. Current practice is to grant

recruit leave on graduation day.)

soft, crimson, brunette and blond tonsorial remains of my Platoon

mates. As we left that building we were indistinguishable one from the

other. We had no individual identity, only shades of color and that

didn't matter. Our only claim to life itself was that we were part of

Platoon 387, Third Recruit Training Battalion, Recruit Training

Regiment, Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina.

Good God, what had I done. No ex-girlfriend's father was worth this.

I'd have gone AWOL if I could have figured out how to do it. (At

Reception, even before we met our own drill instructors they were kind

enough to tell us that it was called Parris Island for a reason--the causeway that our bus brought us in on was the only land link and it was guarded by real Marines with 45 cal. pistols

and riot shotguns. The swamps around the island were populated with

hungry 'gators who long ago had developed a taste for young recruits.

Our choices for leaving the island were: 1) in the belly of a 'gator,

2) in a pine box, 3) in both custody and disgrace or 4) as a United

States Marine sitting proudly in a Greyhound bus enroute to Infantry

Training at Camp Geiger,

North Carolina). [In 1963, when I graduated as a Marine, boot camp

leave was not granted until after MCT. Current practice is to grant

recruit leave on graduation day.)

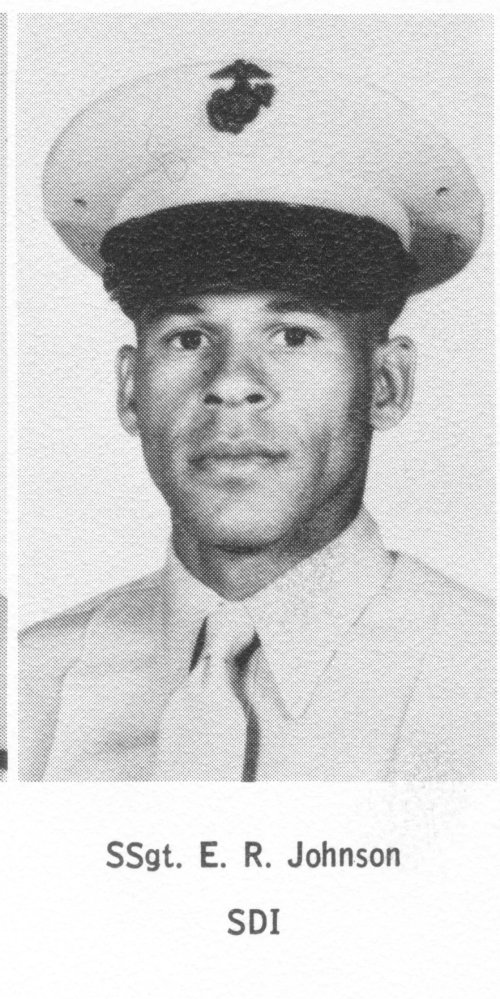

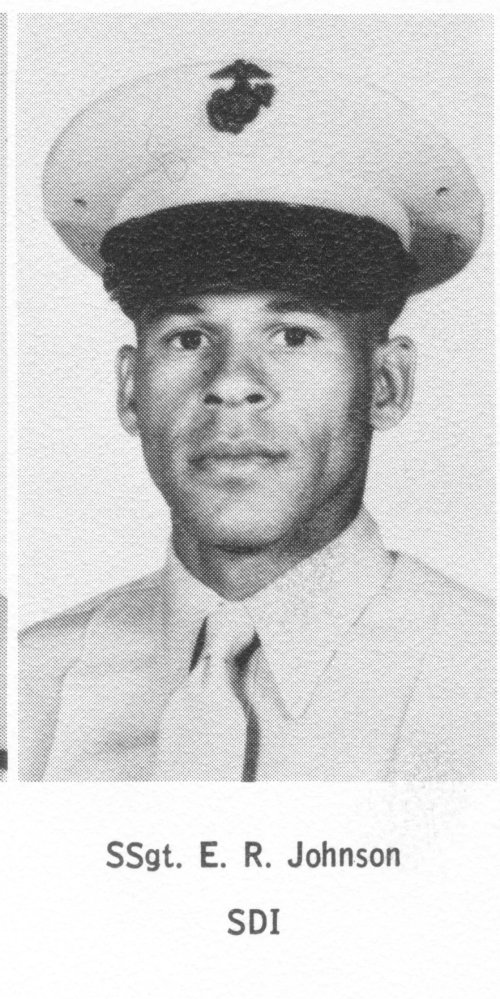

Staff Sergeant

Eddie Johnson, black (remember I came from Lititz, Pennsylvania and had

to drive to Lancaster's 7th Ward to see a 'Negro'), a survivor of the

Frozen Chosen in the Korean War and at 5 feet and a few, looked more like the  Marine Corps Bulldog than "Chesty" (See Note 1) himself, was my senior Drill Instructor.

Jack Webb not withstanding, if there are DIs in this world they are all

at that other depot where recruits were issued sun glasses and tanning

lotions--make no mistake these guys are DRILL INSTRUCTORs. Calling one

a DI would evoke a monologue involving Jack Webb, John Wayne and other

pseudo-Marines along with the offer to "ship you to Dego (San Diego,

California)" where they would turn us into Hollywood Marines vice the

real Marines (who could only be created at Parris Island)

Marine Corps Bulldog than "Chesty" (See Note 1) himself, was my senior Drill Instructor.

Jack Webb not withstanding, if there are DIs in this world they are all

at that other depot where recruits were issued sun glasses and tanning

lotions--make no mistake these guys are DRILL INSTRUCTORs. Calling one

a DI would evoke a monologue involving Jack Webb, John Wayne and other

pseudo-Marines along with the offer to "ship you to Dego (San Diego,

California)" where they would turn us into Hollywood Marines vice the

real Marines (who could only be created at Parris Island)

But something was not quite right. My

"Guidebook for Marines" had a section in it showing rank but for the

life of me Sergeant Johnson's rank was not shown. Neither were the rank

insignia of my other two drill instructors, Sergeant Nicolopolus and

Corporal Frank. The pictures in my guidebook did not have crossed

rifles. I knew right away that the Senior Drill Instructor in our

sister platoon was a gunnery sergeant (three up, two down and nothing

in between that space was reserved for stars, diamonds and bursting

bombs). The Marine Corps was in the middle of changing its rank

structure to add three more pay grades to conform to the Department of

Defense grade structure). Sergeant Johnson cleared it up for me and I

was offended that not only had I been issued a defective Guide Book but

also I was going to have to pay for it, along with the other items in

our PX issue, from my first pay check (at this time I was struck with

the thought, "Gee, all of this and pay too"). Hell, I was really mad

when I learned that I would also pay for my "haircut". As I was

inquiring inwardly on the state of justice in the Corps I was quickly

learning that there is no such thing. There is only stark reality. I

would soon learn that the first person you turn to in trouble is

yourself, often relying only on the knowledge and instinct that drill

instructors, marksmanship instructors, platoon sergeants and your

fellow Marines have taught you. It all starts with taking care of

yourself. You know for certain that your buddy can't help you if he is

wounded or dead and you can't help him if you can't function.

Boot camp it turned out was 13 weeks of

threats, sweat, physical and emotional abuse, deprivation, horror,

fear, loathing and ugliness I hated it--and I loved it. The discipline

of 80 booted feet striking the ground together each second, being able

to respond to non-words barked as commands, learning to place your

ultimate trust in another Marine, feeling your body harden, learning to

take strength from small successes and at the end, having a Marine

reviewing officer say, "Dismissed Marines"------there is no word for

that feeling and once you've experienced it, you never forget it.

The Third Battalion was then known as

Disneyland (mostly because we were housed in new brick, three-story

buildings which by now permeate the whole island). The Second

Battalion, across the main street from the "largest grinder in the

world", was Dodge City (with War II wooden two-story barracks). For the

life of me I can not remember what we called First Battalion, on the

bay side of the drill field, AKA grinder. After 30 years I have finally

decided that the only advantage we had was an easier to clean squad bay

and head.

As one of the tallest recruits I started out

as a squad leader until I screwed up (it took about two and a half

hours as I recall) and I never filled any leadership position after

that. So much for five years as a Civil Air Patrol cadet. The early

days of recruit training sort of meld into one big platoon-sized mass

with few high points. I do recall that I was a boot just a little over

a year after Gunnery Sergeant McCune lost four of his recruits in the

PI swamps while on an unauthorized night training exercise. The

recruits panicked and didn't follow orders but the drill instructor was

Court Martialed and demoted and field training in boot camp was

downgraded to an over-night bivouac at Elliot's Beach. The field

training was moved to Camp Geiger, which is adjacent to the New River

Marine Corps Air Station and across the bay from Camp Lejeune,

North Carolina. Sergeant Johnson summed it up rather susinctly, "It

takes 13 weeks to make a Marine out of you, we make you a soldier in

four weeks". I never doubted it.

Another outcome of the McCune incident was

that Drill Instructors were counseled to stop abusing recruits,

profanity was to be avoided, summary physical punishment would get a

drill instructor a severe reprimand. Given this, Sergeant Johnson had

us form a tight circle around him inside our squad bay as the two

junior drill instructors watched the entrances for one of the many

newly assigned lieutenants whose job it was to catch a drill instructor

treating a recruit badly. Sergeant Johnson calmly explained all of the

new rules and then announced that such rules make the training of real

Marines impossible--but he gave us a choice. If we wished them to, our

drill instructors will train us by the rules but none of us would

really be Marines when we graduated--we would be marines. Conversely, they would ignore the rules within the confines of the squad bay and make real Marines,

out of us. If we chose the second option we had to swear solemnly never

to violate the "code of silence". I felt like a player in a comic opera

as we all shouted, "Make us Marines!" I fully expected John Wayne, Chesty Puller and the Marine Corps Band

to sneak into our midst and congratulate us for holding to a centuries

old tradition of God, Country, Motherhood and Physical abuse of

recruits. Our drill instructors were true to their word and I was one

of the people most aware of that painful fact by the end of 13 weeks.

Discipline was meted out at the whim of the

Drill Instructor and you felt that they got some sort of perverse

pleasure out of seeing us in pain. "Extended Port" was a regular

favorite. At the position of attention we would bring our 9 pound M-14

rifles to port arms and then fully extend our arms. It took only a few

minutes for the strongest of us to feel the agony in our out-stretched

arms. It was particularly difficult for me given my state of physical

non-conditioning. (On my initial strength test I was able to barely

make the minimum of one pull-up but at the final strength test I did

post a 100% improvement). Other forms of punishment included watching

TV. To watch Channel 2 we would position our chin in our hands and our

elbows on the linoleum floor and our toes holding our bodies off the

ground. Channel 6 involved "sitting" a few inches off our bunks

supported by our locked arms. There were others but they were all

similar in design and effect.

Our only break from the incessant glare of our

drill instructors was on Sunday mornings when we got the chance to

attend worship services. At that time each battalion had its own

chapel, ours was in a Butler-type building at the far end of our small

drill field or grinder. We learned quickly that we could go to Sunday

services and sit down for a few hours away from the glaring eyes of our

drill instructors, or we could stand at attention at the end of our

racks for those two hours--as we did whenever there was no training

event scheduled. We almost all went to chapel. I found a second benefit

to attending services, I could send the bulletin home to my grandmother

who never understood why I wanted to join the "Army" in the first

place--but if it led to my attending church, she was happy about it.

Later that day we had "free time" to wash our clothes by hand on the

concrete wash racks and hang them using the "tie-ties" (small pieces of

string with metal clamps at each end to keep them from un-raveling) we

had purchased in our PX issue. Washing machines and clothes pins were

things to dream about. Our utility uniforms didn't see starch until we

were almost ready to out-post--until then we looked much like human

olive drab wash cloths (very similar to how we felt about ourselves).

About a week into

our training the M-14 rifles became our closest companions. Soon after

they were issued I found myself having trouble sleeping. My bunkie--a

6' 3" gorilla with the personality of a gnome--was a friend sort but

also someone to be feared. Minutes after hitting the racks I was on the

top bunk I would feel the bed moving back and forth at a rate which is

well known by any American male who has reached puberty. After a week

of this I summoned my courage and peered over the side of the mattress

to see my bunkie methodically jerking his hand up and down rubbing

linseed oil into the wooden stock of his rifle. With a sigh of relief I

learned to enjoy being rocked to sleep and I smiled whenever an

inspector complimented him on the shine of his rifle stock. (See Note 2)

South Carolina winters are warmer than

Pennsylvania winters but the effect of damp cold air is absolutely

numbing. Sergeant Johnson, frost-bit in Korea's Chosen march would show

up for January morning formations with thermal underwear, woolen undershirt, poplin sweater, battle jacket (the Army

called them Ike jackets but General Eisenhower has never been popular

with Marines), scarf and field jacket along with two pairs of gloves.

He must have served as the model for Bill Cosby's Rudy in the cartoons

two decades later. I think the cold might have killed me had it not

been for his stoic presence.

underwear, woolen undershirt, poplin sweater, battle jacket (the Army

called them Ike jackets but General Eisenhower has never been popular

with Marines), scarf and field jacket along with two pairs of gloves.

He must have served as the model for Bill Cosby's Rudy in the cartoons

two decades later. I think the cold might have killed me had it not

been for his stoic presence.

Johnson was quiet with strong piercing eyes

and a hair trigger temper. When angered he would mix metaphors and

profanities into a tragic comedy of theatrical hyperbole. He would

march up and down the foot lockers placed in front of our bunks just

before lights out in the 30 minutes we had to shine shoes and brass,

polish our rifle stocks, receive remedial instructions, clean the head

(Navy for toilet), brush our teeth, shower and write home. The Corps

listed it on the training schedule as "Free Time". At one point the

diminutive drill instructor was so mad with the average sized

Kentuckian across the bay from me--Adam Victor by name--that he jumped

onto his foot locker, looked the offender straight in the eye and

managed to offend Victor's mother, virtually all deity and common

decency without taking a breath. Then grabbing two pillows he turned

them into puffy cymbals and he tried to create a great crashing sound

with Victor's head between them. I thought the man certifiable at the

time yet, even today, I would follow him into Hell itself without

question. Don't ever ask me why!

Nicolopolis was another case for study at a state institution. Not until years later as I watched the Evzones Guards

in Athens, Greece did I fully understand Sergeant Nick. These men in

tasseled caps, wooden, pointed and tassel tipped shoes, bright white

lacy skirts and tights stood so straight as to be approaching a

backward tip. They are also among the world's most feared fighters and

Sergeant Nick was at one with them--in our ranks.

On our return from two weeks on the firing

range Sergeant Nick had us fix bayonets, come to extended port and

double timed us the two miles back to our squad bay. As we halted,

ordered arms and did a left face he quickly put us at extended port

again and then walked directly past me while degrading us as the worst

shooting platoon he had ever had. At the moment he passed in front of

me my mind commanded my arms to thrust, putting the bayonet directly

into his back. The muscles in my arms wanted to obey but could

not--thank God. I am certain that had I been physically capable I would

have killed or seriously wounded one of my junior drill instructors.

Today I have immeasurable respect for him and what he did for me. At

the time he was a perfect enigma.

Just before Christmas we started getting

packages from home. Cookies could be either shared with the platoon or

eaten in a single sitting by the recipient. Most chose to share while

others weren't given an option. Gum was pogey bait and consigned to the

dumpster. But in my case, they had no idea what to do my mother who

then worked at Warner-Lambert sent me a case of Certs

breath mints. I have no idea why and she now denies ever sending it. I

did have the most kissable breath in the platoon for a long time and

the only one to get a kiss was my Kentucky friend who managed to put

his emblems on backward for our first greens inspection. Sergeant

Johnson kissed him right on the lips and pronounced him queer because

"only a queer would wear his emblems with the anchors pointing out". I

know I'll never forget that lesson.

As the Christmas

goodies continued arriving we went into holiday schedule with only one

drill instructor on duty at a time. Sergeant Nick was on duty the day

the House Mouse--a college-educated, brown-nosing, Chicago boy--(See Note 3)

got two fifths of whiskey in the mail. Nick marched him directly to the

dumpster where the bottles were un-corked and the contents poured out.

As he was being relieved the next morning we heard Corporal Frank in

the DI house yell, "You ignorant sheep-fleecing son of a bitch, you

actually dumped the whole damned bottle?" Followed by a plaintive,

"Two?".

Corporal Frank was a heavy equipment operator

who had eight years service and sergeant stripes when he got out of the

Corps and lost a stripe on reenlisting. His mania was the head and he

took a personal interest in the head cleaning detail. (Remember, we are

talking Naval head, as in toilet) At some point there was a problem in

the head and Frank yelled out, "Give me one member of the head detail,

now." No one responded and without even appearing through the hatch

(the Navy calls a door a hatch) he commanded, "Give me the whole

expletive deleted head detail right now". They all responded and one by

one they waited outside until a big hairy arm would reach out, clutch a

shirt, lift the body six inches off the deckand pull it, like a rag

doll, into the head. I have no idea what went on in there but people

responded to his future calls.

The heads in the Third Battalion buildings

contain a squad shower, drying room, about six stalls and four urinals.

Head calls were only allowed on individual request--which was done only

in case of a dire emergency--or in a group of 35 at a time. Usually you

ended up standing in line at the urinals. On one occasion the 300 pound

half gorilla named Edward C. "Brownie" Brown was standing behind me

goosing me, trying to get me to yelp. Remember, at the time I was

poster boy for the 98 pound weakling club. After a couple of jabs I

just put everything I had into my elbow and struck him in the middle of

his chest. He crumpled to the floor, breathing but in serious pain.

Suddenly everyone decided they really didn't need to go after all and

exited en mass. The hasty retreat piqued the curiosity of Corporal

Frank, himself a woolly mastodon. (I started making my peace with my

maker because I was surely to die that day.) Frank entered the head,

looked at my scrawny body, looked at the mass of pumped and pained

flesh on the floor, looked back at me, again at Brownie, shook his head

and walked out. Nothing further was said. I am certain that my maker

wanted me to feel close to death but was saving me for much greater

pain to come.

Frank had an

interesting sense of humor. After our first day of live fire on the

rifle range he offered "group tighteners" to anyone who felt their

shooting was not up to par that day (See Note 4)

. About a dozen souls reported for the training and after they were all

lined up in front of him he balled his fist and pounded it firmly into

the upper chest of the recruit in front of him. The recruit collapsed

and Frank stepped across to the next and then the next until all were

administered. As they were recovering and staggering back to attention

at the foot of their racks Frank announced, "Groups gonna be tighter

tomorrow, aren't they?" The next day there were no takers when the

offer was made again. Surprisingly I was not one of the "trainees" in

the unofficial elective.

I'm not certain but I think that the drill

instructors are required to find and develop a platoon screw-up someone

for us to hate (other than our drill instructors). Ours was Jonathan G.

Wallick short and fat (I think he joined us late from conditioning

platoon), in the obstacle course competition I never did see him

finish. We were told that Cpl. Frank stayed with him until he finished,

some three hours after we marched back to our squad-bay. We were also

told that he was responsible for our platoon loosing the drill

competition and on the day we were to be inspected in our dress green

uniforms he was sent on some kind of detail in utilities. He returned

just in time to be included in our platoon photograph in utilities

while the rest of us were in greens. I remember that some members of

our platoon gave him a "blanket party" I slept through it. I've always

wanted to meet up with him again to find out what kind of Marine he

became. [A brief email response to this request informed me that he

left the Marine Corps at the conclusion of his tour as a Sergeant of

Marines--same as me. I really would like to hear from him again so I

can tell him that I felt sorry for him in boot camp and am happy that

he had a good tour.]

As we headed into Christmas, boot camp became

even more of a surreal experience. Since almost everyone was on leave,

two weeks of training was virtually eliminated. Anywhere else in the

world that would be good news, but at this time in Marine boot camp,

when a recruit was not in organized training he was standing at

attention at the foot of his bunk reading and memorizing the eleven general orders (my dad, a World War II soldier, and I astounded each other recently when we both recited all eleven), the Marines Hymn

(I can still sing three verses from memory), the Department of Defense

wiring diagram and rank insignia or the nomenclature of the M-14 rifle,

Browning Automatic Rifle or the 50mm Machine Gun. For two weeks that

routine was broken only by breakfast, lunch and dinner as well as the

infrequent drill sessions. But on Christmas eve we saw a movie at the

base theater and then massed in front of depot headquarters to serenade

the commanding general. It was a pleasant break and our singing made

Nick and Frank feel generous so on the march back to the squad bay they

left us quietly hum the Marine Corps Hymn. It was a rush second only to

the "Dismissed Marines" command at graduation.

In the week before graduation I learned that I

would be going either to embassy duty or sea duty both highly sought

after special assignments. A letter told me that my mother, my sister

and my grandparents would be coming down for graduation. There was

almost no training and we were spending entire days again at attention

at the foot of our racks. Only one drill instructor was on duty and it

was not un-common for them to leave us alone in the squad bay for hours

at a time. Sergeant Nick left by the front ladder (Navy for stairs),

which we were never allowed to set foot upon, and 15 minutes later I

was eyeing the column just to my right between me and the hatch my

drill instructor had departed through. After much soul searching I

decided that no one would be killed if I were to kneel behind that

pillar. I did and my comrades were in awe of my courage. After about

five minutes in that restful position, all the time watching the hatch

(AKA door), I heard a muffled tap tap of metal cleats on linoleum.

Looking back under my arm I saw a brightly polished pair of brogans

approaching and then the biggest pain in the ass anyone has ever had.

It lifted me off the ground and into the top rack on the other side of

the squad bay. But the most lasting pain was finding out that I had

earlier impressed Frank and he had recommended me for PFC. After that

incident I was happy to graduate a private.

Look out world, here comes Marine Private Glenn B. Knight, 65 pounds of additional muscle, a gung ho attitude and a lot to learn.

Join me for my adventures in the only war that I took part in, the Dominican Republic in 1965.

Notes:- Chesty

(Roman numeral something or another) was the name of the bulldog that

would show up, from time to time at parades and formations. I recall

that he was a lance corporal (and as a result outranked all recruits)

and that he was named for Lieutenant General Louis B. "Chesty" Puller,

then retired and living in Arlington, Virginia.Return

- Keep in mind that in 13 weeks I never had the

opportunity to talk to most to the members of our platoon. The only

time we had to talk was a few minutes after chapel, during our daily

30-minute free-time and following graduation. Every other minute of the

day was spent at attention or in some form of activity. Social

discourse was not part of the training regime and we did not get to

really know anyone in our platoon. Most people can't appreciate the

absolute and total loss of freedom.Return

- House Mouse--a member of the platoon selected

by the drill instructors to provide personal services to them. This

recruit would keep the drill instructors' room in order, make up their

racks, make and fetch coffee and run other erands. In return the mouse

was usually excused from fire watch and other regular duties. In

additionally, they usually got one of the Private First Class stripes

given at graduation to the most outstanding recruit.Return

- The object of rifle training was to get all

of your rounds into a small circle, or "group". It did not matter where

on the target that group hit because the sights could be adjusted to

bring the group into the center bull's eye. The early emphasis was on

tight groups, not on making bull's eyes. Return

Return to Glenn Knight's Home Page

Return to Glenn Knight's Home Page

2/12/98 GBK

http://4merMarine.com/bootcamp.html God

in his dress blues) started filling me in on the advantages of the

Marine Corps. After checking my scores to make sure I wasn't just

bothering Sergeant Crim, he offered to deliver a message. Before my

next, and last trip, to see the Air Force Recruiter I had an argument

with a former girlfriend's father, an ex-sailor, who called me a wimp.

I decided then to get into the service, do my time, get out and become

a Pennsylvania State Trooper

to prove to him that I was no wimp. Unfortunately, I was more than 6

feet tall, weighed in at just over 100 pounds and never played

sports--sort of your classic wimp.

God

in his dress blues) started filling me in on the advantages of the

Marine Corps. After checking my scores to make sure I wasn't just

bothering Sergeant Crim, he offered to deliver a message. Before my

next, and last trip, to see the Air Force Recruiter I had an argument

with a former girlfriend's father, an ex-sailor, who called me a wimp.

I decided then to get into the service, do my time, get out and become

a Pennsylvania State Trooper

to prove to him that I was no wimp. Unfortunately, I was more than 6

feet tall, weighed in at just over 100 pounds and never played

sports--sort of your classic wimp.

At

that point life went on automatic and fear numbed me as we were

"greeted" on the platform of Yemassee Station and as the "cattle cars"

(actually 40 foot tractor-trailers converted to haul human cargo) drove

us to reception, some 30 miles away at Parris Island, South Carolina. A

trance took me through everything Sergeant Coconis had warned me about

the search for alcohol of any type (including after shave and cologne)

and pornographic photos (that list started with photos of girl friends)

and "POGEY BAIT" all of it confiscated. Linen and PX issue (with drill

instructors walking the cat-walk above the bins in front of us yelling

insults and calling us "lower than whale shit" and "ladies") was all

taken in stride. Even jumping in and out of bed about a bazilion times

before we were allowed to sleep until what I was later to hear

described as "Oh-Dark-Thirty". I slept like a baby until Pearl Harbor

was reenacted in our echo-chamber of a squad-bay. All three drill

instructors had positioned themselves with a metal GI can over their

heads and, at reveille, they threw them on to the linoleum floor as an

inducement for us to rise, strip our beds of linen and covers and

appear in our underwear at the foot of our beds (A.K.A. racks). Fear

was growing rapidly but the reality of the situation had not yet set

in.

At

that point life went on automatic and fear numbed me as we were

"greeted" on the platform of Yemassee Station and as the "cattle cars"

(actually 40 foot tractor-trailers converted to haul human cargo) drove

us to reception, some 30 miles away at Parris Island, South Carolina. A

trance took me through everything Sergeant Coconis had warned me about

the search for alcohol of any type (including after shave and cologne)

and pornographic photos (that list started with photos of girl friends)

and "POGEY BAIT" all of it confiscated. Linen and PX issue (with drill

instructors walking the cat-walk above the bins in front of us yelling

insults and calling us "lower than whale shit" and "ladies") was all

taken in stride. Even jumping in and out of bed about a bazilion times

before we were allowed to sleep until what I was later to hear

described as "Oh-Dark-Thirty". I slept like a baby until Pearl Harbor

was reenacted in our echo-chamber of a squad-bay. All three drill

instructors had positioned themselves with a metal GI can over their

heads and, at reveille, they threw them on to the linoleum floor as an

inducement for us to rise, strip our beds of linen and covers and

appear in our underwear at the foot of our beds (A.K.A. racks). Fear

was growing rapidly but the reality of the situation had not yet set

in.

soft, crimson, brunette and blond tonsorial remains of my Platoon

mates. As we left that building we were indistinguishable one from the

other. We had no individual identity, only shades of color and that

didn't matter. Our only claim to life itself was that we were part of

Platoon 387, Third Recruit Training Battalion, Recruit Training

Regiment, Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina.

Good God, what had I done. No ex-girlfriend's father was worth this.

I'd have gone AWOL if I could have figured out how to do it. (At

Reception, even before we met our own drill instructors they were kind

enough to tell us that it was called Parris Island for a reason--the causeway that our bus brought us in on was the only land link and it was guarded by real Marines with

soft, crimson, brunette and blond tonsorial remains of my Platoon

mates. As we left that building we were indistinguishable one from the

other. We had no individual identity, only shades of color and that

didn't matter. Our only claim to life itself was that we were part of

Platoon 387, Third Recruit Training Battalion, Recruit Training

Regiment, Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina.

Good God, what had I done. No ex-girlfriend's father was worth this.

I'd have gone AWOL if I could have figured out how to do it. (At

Reception, even before we met our own drill instructors they were kind

enough to tell us that it was called Parris Island for a reason--the causeway that our bus brought us in on was the only land link and it was guarded by real Marines with  Marine Corps Bulldog than "Chesty" (

Marine Corps Bulldog than "Chesty" ( underwear, woolen undershirt, poplin sweater, battle jacket (the Army

called them Ike jackets but General Eisenhower has never been popular

with Marines), scarf and field jacket along with two pairs of gloves.

He must have served as the model for Bill Cosby's Rudy in the cartoons

two decades later. I think the cold might have killed me had it not

been for his stoic presence.

underwear, woolen undershirt, poplin sweater, battle jacket (the Army

called them Ike jackets but General Eisenhower has never been popular

with Marines), scarf and field jacket along with two pairs of gloves.

He must have served as the model for Bill Cosby's Rudy in the cartoons

two decades later. I think the cold might have killed me had it not

been for his stoic presence.

Return to Glenn Knight's Home Page

Return to Glenn Knight's Home Page